A lot has moved on since I outlined ’12 things to think about’ in a 2016 blog. That is certainly true of the world around us, the focus and central concern of Geography. It is also true of the ways in which primary schools are thinking about their foundation subjects.

The following is written with subject leads in mind, although it will hopefully be useful to other primary teachers as well. It refreshes the 2016 ideas and reflects on present priorities for Geography, guided by the first of the three main headings from the Ofsted inspection framework: Intent.

I will look at Implementation and Impact in a follow-up blog.

Intent

What will pupils be learning? What knowledge, understanding and skills do we anticipate that they will build up as a result of our plans?

Behind those questions is another implicit question: what’s it for, Geography in our school?

The 2014 National Curriculum states that geography ‘should inspire in pupils a curiosity and fascination about the world and its people that will remain with them for the rest of their lives’ (this is in itself quite an inspiring thought: the same curriculum says something similar about History and Science). So, it is worth thinking about how the school’s curriculum can live up to that aspiration, on paper and in practice.

It is also worth thinking about the needs of the school, the children and the local catchment:

- Are there particular opportunities that Geography should be providing?

- Perhaps the children live in a bit of a ‘bubble’ and need experience of the world beyond their immediate neighbourhood? Or perhaps they are generally well-travelled but still have limited insights into lives different from their own?

- Maybe there are open spaces or landmarks that can provide a focus?

- What are the top priorities for these particular children in this particular school?

This helps us focus on the things that really matter when it comes to organising the school’s curriculum. For example, it may be important to maximise direct experience of the world through additional fieldwork opportunities. Articulating such school-specific priorities can also be used to formulate a subject statement.

Place-based planning

With purposes and priorities in mind, how best do we structure curriculum coverage? As I suggested in 2016, you could consider “putting place at the centre of our planning: localities at KS1, regions at KS2. It’s amazing how much can slot in around those places, which in turn afford a clear context for skills, processes, concepts and locational knowledge.” These places form substantial blocks around which other themes and topics can be ordered.

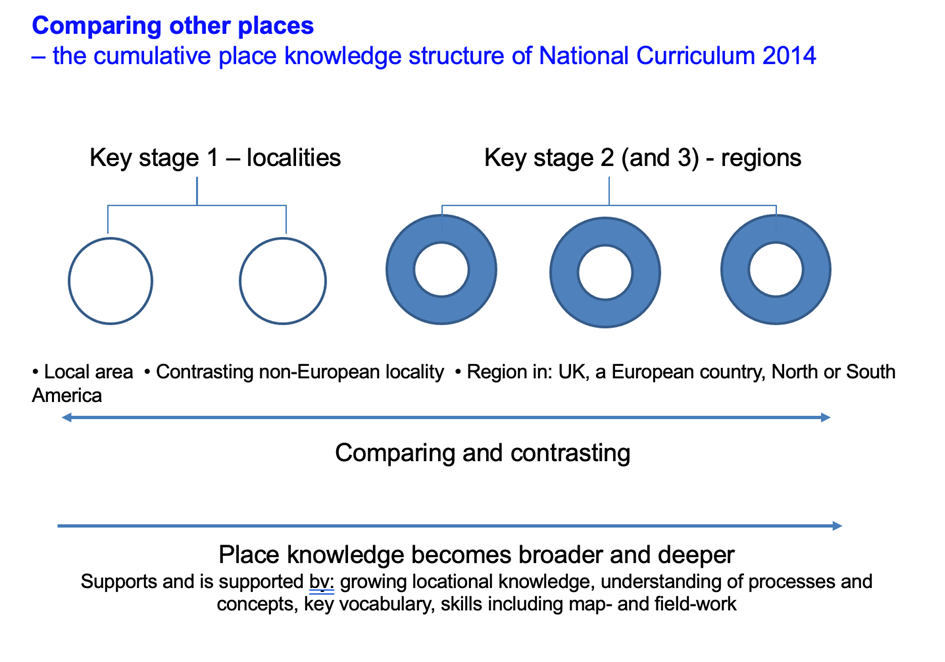

As the diagram below shows, place and locational knowledge requirements in the 2014 National Curriculum broadly highlight the same areas of the world. This knowledge is organised cumulatively: knowledge of each new place builds on prior knowledge of places already studied. A key emphasis in all of this is making meaningful comparisons between places on a similar scale: between the local area and a similar-sized locality at KS1, between regions at KS2.

This builds in an element of sequencing and progression: by the time pupils are investigating their third region in upper Key Stage 2, they will have insights into at least two other regions and two localities to draw on. They will grow their understanding of what makes those places ‘tick’, how they differ from or resemble each other, and also increase their confidence in engaging with the geographical language, images, concepts, processes and tools that are available to help understand them.

What’s the story?

On sequencing, Ofsted’s 2021 Research Review for Geography asserts that “As pupils progress through their school years, they develop their knowledge from specific examples to generalisations that they can apply in different locations.” So, new knowledge and skills not only build on the places that have been taught before, their location and key features, but also support greater fluency in engaging with Geography’s big ideas and key concepts.

That might sound a little scary, but in practice it encourages us to avoid getting too bogged down in the itty-bitty detail. As I said in 2016, “if we can’t say, in plain English, what the main things are that we hope pupils to learn in each year, then we have probably made it too complicated. Imagine a chain story: the teacher of the next year group upwards should be able to pick up what we have just said and add their own sentence to it. For example, ‘pupils came into the year knowing this and being able to do that, and by the end of my year they will also know these other important things and be able to do these other main things.”

Another way of describing those ‘main things’ is as learning outcomes to be attained by what Ofsted describes as ‘defined end points’ (e.g. the end of each main Geography-led topic). As the story progresses, we should be able to see the learning getting both broader (e.g. more places, more issues, more skills) and deeper (e.g. greater understanding, more sophisticated use of geographical language and concepts, more effective and confident mapwork, fieldwork enquiries etc). It is worth noting that reports from Ofsted have highlighted the crucial need for regular, purposeful and focused mapwork and fieldwork, especially at Key Stage 2. These aspects of Geography help bring apparently abstract ideas to life and make them memorable.

Because there are no nationally determined Age-Related Outcomes for Geography, it may be useful to moderate the school’s expectations for pupils against benchmarks such as those provided in the Geographical Association’s progression framework. For those using the TTS Teaching Atlases, the supporting framework will also be useful.

Time enough?

Having established a broad sequence of Geography-led units and the principal learning outcomes arising from them, we can move onto thinking about the individual units. Decisions about interleaving vs blocking subjects, organising time around cross-curricular topics or through single subject teaching, will probably have already been made by senior managers. While there is a growing trend towards single-subject teaching, especially at KS2, what really matters is that it is clear that learning is explicitly geographical and that sufficient time is given to cover the skills, knowledge and understanding involved.

Although the 2014 National Curriculum is dramatically slimmed-down when compared with the original Programmes of Study in the late 1980s, many schools express continuing anxiety about ‘curriculum overload’. However, three geography-led topics each year will normally be sufficient, as long as there are opportunities to ‘top up’ and consolidate skills, vocabulary and knowledge between these times. I am increasingly seeing schools alternate a half term of Geography-led learning (6-8 lessons) with a half term of History, sometimes allowing sophisticated bridges to be made between the two (e.g. a Nile study forms part of a ‘Rivers’ unit, which then feeds into work on the Ancient Egyptians; historical maps are used to investigate settlement processes and as historical evidence in a local area enquiry). Many schools choose to have a ‘fieldwork week’ in the Summer term, supporting varied activities across all year groups.

So, having got the curriculum ‘ducks’ in a line, what next?

The next blog (part 2) will look at Implementation and Impact.

With many thanks to Ben Ballin for writing this blog.

Ben Ballin is a primary consultant specialising in geography and global learning. He is the author of the TTS Upper Primary Teaching Atlas.