Getting the correct balance

In recent times, there has been immense pressure on schools to “perform” and it can be incredibly difficult to balance what is needed for addressing the issues around mental health alongside academic expectations, but these are intrinsically linked: How can a child achieve their best when their thoughts and feelings are out of sync? Similarly, when the focus of learning is mainly on English and Maths, some children are going to suffer. Some schools are treating other subjects as occasional treats or add-ons, rather than including them in a broad and balanced curriculum which is more likely to meet everyone’s needs.

Circle Time

I was once asked by a headteacher whether half an hour on a Monday morning spent having Circle Time with a class of troubled Year 6 children was “an effective use of time”. A number of these children had spent each weekend either being exposed to inappropriate influences or being kept inside the household to avoid this happening. Amongst other things, they spoke of being frightened in case people broke into their homes, that the sounds of shouting and violence outside during the nights terrified them and a myriad of other worries. By holding a Circle Time on their return to school, they were able to talk about their experiences in a safe, controlled space. They knew that others had listened to them and cared about their thoughts and feelings, were able to advise them etc. This enabled us to move on to work with children’s heads a bit calmer and clearer. Needless to say, the Circle Time sessions continued.

Denmark and the USA

In some countries, social skills are seen to be a key part of children’s schooling. For example, in Denmark (which often features in the top 3 happiest countries in the world) it is mandatory that children are taught empathy from kindergarten. The approach includes explicit teaching, anti-bullying programmes, and very careful pairing of children with different personalities and strengths.

There are schools in many countries which are including teaching children mindfulness. Some inner-city schools in the United States have implemented meditation in place of detention or time out. This takes place, not in a sterile windowless room, but in a colourful space full of soft furnishings. They have also offered yoga classes after school. Creating community gardens is another initiative providing positive benefits for the mental health of all involved.

Approaches in school and at home

The ability to address children’s needs can be adversely affected by a number of factors: home and school circumstances, staffing issues, expectations of what the purpose of school is, parents’ experiences and approaches.

One family I know have 3 boys: 8, 6 and 3 years old. The boys have been brought up to communicate with each other. They talk to each other when there is a problem rather than being conditioned to immediately involve adults to solve difficulties, e.g., “Please can you not make noise in the kitchen when I am doing my homework because I can’t concentrate.” They are able to state the problem and the reason why it’s an issue. Not all parents have the skills to be able to model and teach their children in this way, which is why it is vital that this work is undertaken by schools.

I have already mentioned Circle Time and its beneficial effects. There are so many different approaches and ideas which can help encourage children to talk within the classroom. For these to be effective, it is essential that the whole school is aware of good practice and that this is a shared responsibility across all stakeholders, be they children or adults, employees or caregivers. Everyone needs to understand the importance of recognising and validating children’s feelings and emotions. Are staff trained to be very observant about the children: Are they displaying a flat affect/seem withdrawn/unusually tearful? It can be as simple as asking if a child is OK, maybe that you have noticed they seem a little down, anything you can do to help, e.g., This can mean offering to make time to talk, which is not always easy in a busy school environment but could be a breakthrough for that child.

Positive Reinforcement

A very powerful strategy is to focus on positive reinforcement re: children’s behaviour towards one another. It is so much more effective to praise “good” behaviour, and being specific about this, e.g., I really like the way you helped your friend when they were upset because I could see it made them feel better/less embarrassed, or, Well done for staying calm, that must have been difficult for you… Of course, there are behaviours that can’t be ignored, e.g., if someone is being harmed by another, but as a teacher, I found myself noticing that when the focus shifted from the negative, it had a beneficial effect on me, and the children involved.

Ownership of mistakes

It is really important to help children to take ownership of mistakes. Having a format to use in these circumstances provides children with a framework to say sorry in a meaningful way, where they can recognise what went wrong.

This is an example of an apology scaffold:

I hurt [someone’s] feelings.

It was wrong because […]

I can apologise and I am sorry for […]

Next time I will […]

Is there anything else I can do?

Today’s Big Question

A key aspect of encouraging children to share their thoughts and feelings is to develop a culture of talking, giving opinions, understanding that there are sometimes no right or wrong answers to questions, simply say what you think and give your reasons.

My classes always enjoyed starting the day with an activity which is known by a variety of different names, but we used to call it Today’s Big Question. Each day, while the register was being taken, a different question would be displayed on the Smart Board. The questions would range from philosophical/moral dilemmas/fun ideas. Children would think about their response during the register, then had a few minutes to discuss their ideas with their next-door partner before quick optional feedback. This really helped children to share their thoughts in an informal forum without the pressure of being in the spotlight. Children were also encouraged to feed back on behalf of their partner if that person felt less confident. This helped reinforce that all ideas were valued.

Obviously, children, like anyone, can be impulsive in their responses to others. Teaching the use of acronyms such as the following can help children to be more thoughtful when speaking/posting on social media.

THINK before you speak/post:

T – Is it true?

H – Is it helpful?

I – Is it inspiring?

N – Is it necessary?

K – Is it kind?

Restorative Justice

This is an idea that has been offered in the prison service for some time, where victims/survivors of crimes meet with their perpetrators to talk through the event and its effects on all parties involved. The primary school version was something the SENCo asked me to trial with my Year 4 class. We had a girl who had self-esteem issues and found it difficult to develop and maintain friendships with her peers as she tended to become possessive and try to control them, leading to ongoing arguments, and allegations of bullying on both sides. With permission from parents, who were all concerned about the situation, we set up a group which would meet weekly. It included the girl at the centre of the issue and the relevant peer group members. As the class teacher, I was designated the neutral mediator. In short, all the children were able to explain how they were feeling about the situation and make suggestions as to how it could be improved. I would make notes and then summarise the ideas for the group. The children were very creative in trying to come up with solutions e.g., Each person in the group would set aside a lunchtime to play with the girl, and establish boundaries for this activity. All parties agreed to the terms and then each week, we would meet and review any progress. The plan was tweaked and refined and proved effective in resolving an issue by allowing the children to take ownership of the situation, where they showed insight and maturity.

Using a Worry Box

One of the things I always included in my classroom was a Worry Box. Children were able to write down a problem or worry that could be brought up for anonymous discussion, for example, during a Circle Time. Recordable devices were also available in case a child was not able to write their thoughts down. This was listened to and transcribed in advance.

These worries could also be written from children in another class seeking “advice” from our class members. I did this before a joint Year 2/Year 6 school journey. This enabled us to raise a variety of issues which could occur, e.g., homesickness, bedwetting, etc. My Year 6s discussed and gave advice for the Year 2s, but this also opened up the discussion as to how to respond if it was one of their Year 6 classmates saying this. Another way to use the Worry Box is that, if you as an adult, feel that someone is experiencing a difficulty, you could introduce this problem into the worry box as if it had been added by a child. This had the dual benefit of bringing this topic into the open, but also it could let the child know that, as they didn’t write it, someone else must be sharing their worry which may have made them feel less alone.

More support

Society needs children who are happy and healthy, physically and mentally, but who also understand that there is a wide range of emotions and that it is OK not to be OK. They need to be taught how to be resilient, and not be subject to unrealistic expectations of their moods. Unsurprisingly, research shows that well-rounded children are more likely to develop into self-aware, balanced adults.

There are great websites for inspiration and support around the issue of children’s mental health, including:

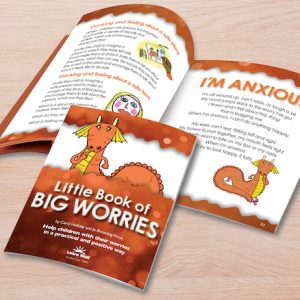

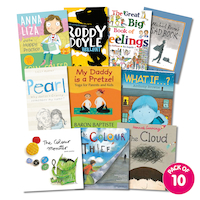

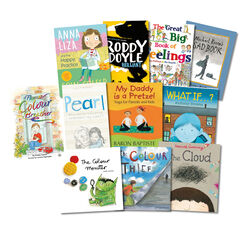

Book recommendations:

- Break The Mould: How to Take Your Place in the World – Sinead Burke

- What To Do When…(series) – Dawn Huebner

- The Happy Workbook: The Feel-Good Activity Book – Imogen Harrison

With thanks to Jayne Gilbert for writing this blog. Jayne is a primary teacher with over 30 years experience and has always been an advocate for the importance of children’s mental health.