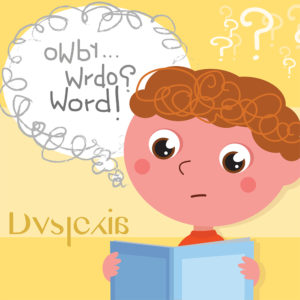

Dyslexia and Early Identification

Following on from Jamie Oliver’s ‘Dyslexia Revolution’ programme (aired in June 2025, on Channel 4), Pamela and Rachel have updated this blog, written back in 2022. Whilst the essence of the blog remains the same- the vital nature of early identification- the updates include reference to the Delphi Study and the new definition of dyslexia, together with updated reference to data related to the rates of dyslexia across the school population and within the penal system.

The BDA recommends that dyslexia should not be diagnosed before the age of seven, many assessors not recommending this until the age of at least eight (or even nine). However, as educators and within our wider lives, we all know of people who were not diagnosed until they were at university and quite tragically, others, who were diagnosed when they were within the prison system. Jamie Oliver’s ‘Dyslexia Revolution’, highlighted the disgrace that we are still in a situation that so many people with dyslexia, leave school ‘not knowing their worth’.

These are emotive points to make, however dyslexia can be very emotive, particularly for those impacted by it. The purpose of this article is to look not at formal diagnosis, which should always be done by a qualified professional, but to remind those in education to ‘trust their spider senses’ when something does not seem ‘quite right’ with a child’s learning and to get support in early. This will not impact upon any formal diagnosis done at a later date and indeed, Rose’s definition of dyslexia (which was adopted by the BDA in 2009), includes reference to: ‘how well an individual has responded to well-founded intervention’. Neil MacKay also highlights that what works well for a child with dyslexia, work well for all children.

So, what are we looking for?

There are roughly five aspects to be aware of, including difficulties with phonological awareness, reading, spelling, memory and processing. The new Delphi definition (2025) has highlighted that dyslexia is characterised as a set of processing difficulties primarily affecting the acquisition of reading and spelling skills, specifically highlighting the tole of orthographic skills (put very simply, a visual process of spelling). It further emphasises that dyslexia exists on a continuum of severity and that it is influenced by both genetic and environmental factors. The new definition highlights the impact that dyslexia can have on a range of other areas within education. What is particularly useful for educators, is the reference to different aspects of phonological processing challenges linked with dyslexia, including awareness, speed, and memory.

Each of the overriding traits, will be taken in turn and explanation given as to what to look for and how we can help with these. It is crucial to bear in mind that these areas may present at varying levels for different individuals and may also be compounded by co-occurring difficulties, such as visual processing challenges, auditory processing difficulties, sensory or even motor-coordination challenges (these really are just a handful of challenges that individuals can experience).

Phonological Awareness

Phonological awareness is the ability to both recognise and manipulate the spoken parts of sentences and words. For young children, this would include being able to identify words that rhyme or recognising alliteration. As children get older, this might relate to their ability to acquire phonics, including segmenting a sentence into words, the word into phonemes, identifying the syllables in a word, and blending these to read them. If a child has been given access to high quality first wave phonics and does not seem to ‘get it’, it is worth considering that there may be a barrier to their learning.

Support

- Multi-sensory learning is an absolute must here, bombard all of their senses when overlearning their phonemes. Then use these practices to work with the phonemes learnt, blending and segmenting. Developing their skills in syllabification will benefit all aspects of decoding.

Be aware that thinking differently is the key here, some children will never learn phonics in the traditional way and may need to use whole word or whole syllable or phoneme recognition, in relation to reading.

Reading

In order to master written language, three areas of phonological processing are generally accepted to be required. These are phonological awareness, phonological memory and rapid naming. This is the rapid retrieval of symbolic information from the long-term memory stores, vital for accurate and fluent reading. Once the building blocks of reading (phonemes) are acquired, a child needs to recognise and manipulate these, in order to read the printed text. They then need to gain understanding from this, to comprehend what they have read.

As educators, we should look at those children who are:

- Very slow to read or will ‘bark at text’.

- Will really struggle to blend to read, despite recognising the phonemes.

Support

- Little and often is crucial to developing this skill.

- It may also be worth considering approaches such as paired reading, using audiobooks alongside written text and so on.

- Assertive technology such as ‘read aloud’ functions and Reader Pens.

- Ensure that the most appropriate text is used for the individual, both in terms of age/ability appropriateness, but also font, sizing, spacing and even colour. A huge amount of assistive technology (often freely available) is also out there!

Spelling

Challenges to the segmenting of words in order to spell them, is a skill in and of itself. The complexities (and beauty) of the English language further compound this.

We need to look for those children who use unusual spelling patterns, whilst many of their misspellings are phonetically plausible, others are not. They may spell words well in spelling tests (after overlearning these and putting in a great deal of effort), however, when writing independently, will make errors. They will often really struggle with the correct use of homophones.

Support

- Once again, multi-sensory learning is incredibly useful here as well as overlearning.

- Building a visual picture of the word, together with discussing and thinking about the number of letters in the word. How many are vowels and consonants? Are there any descenders or ascenders in the words etc.

- The skill of syllabification will really help to improve spelling.

- Many children really benefit from looking into the morphology of words.

- Developing memory techniques will also really help.

Memory

The ability to recall learned information, together with retaining shorter pieces of information for long enough to manipulate it (such as when we are trying to comprehend what we have read or complete mental calculations in mathematics), is a skill.

Those children who struggle to retain verbal instructions or who cannot recall previously learnt information are impacted by this. In addition, changes to examinations in recent years, particularly for older children, means that all children, and not just those who struggle with this, will benefit from developing their memory capability, to retain and retrieve learnt information.

Support

- Establishing the areas of memory a child struggles with most can be really helpful in tailoring the support they need. A simple assessment of this can be carried out to establish a baseline and areas for improvement. For example, testing how many digits a child can remember both in a forwards direction and backwards assesses not only an individual’s auditory memory but also their auditory working memory. To assess visual memory skills, the child can be presented with a number of items visually and asked to recall them once taken away from sight. With both of these tasks, the number of digits/items should start off small and gradually increase. To look at sequential memory, the individual could be asked to remember what they hear or see, sequentially.

- Whilst research into working memory capability suggests that this is relatively ‘fixed’, many areas of memory can be improved by working on this in a ‘little and often’ basis. Improvements can be made with just ten minutes per day. The strategies developed for supporting memory can also be incredibly beneficial in all walks of life.

Processing

Here we will not focus on visual or auditory processing specifically, but more generally on the ability to process information that is being learnt.

Many children will struggle to process what they are trying to learn. They will need to do tasks or have things explained a number of times before they can do this effectively.

Support

- Chunking information can be incredibly effective in supporting those who struggle with processing. Two or three pieces of information should be given clearly and repeated. It is important to repeat this in the same way. Saying things differently, can actually cause further confusion as this appears as new information to be processed.

- Again, using a multi-sensory approach can really help, visual prompts and timetables are useful too.

- Metacognition, teaching children how they learn, can also support their processing.

And finally …

You will do no harm, supporting children who you have concerns with, so be aware, trust your instincts and support them. If you only take away one message from this, please note the sheer amount of effort some of these children are putting in every day, just in order to process their thoughts and learning, be organised, to read, spell, recall previously learned information and so on. It is no wonder that these children will often be exhausted, or even champion prevaricators (repeatedly sharpening pencils or ‘looking’ for books…). This is also often compounded by them being given additional work and tasks to do at home, on top of general homework tasks, which can frequently take them longer to complete.

Be aware of this, be kind to these children and support them.

The ‘Dyslexia Revolution’ highlighted the lack of a statutory system in place to screen children for dyslexia, together with underfunding and under-resourcing in school and very limited training for teachers. Perhaps the way forwards is to focus (at least until these other, often costly, elements can be put in place), on adaptive teaching. Whilst the review of the National Curriculum takes place, maybe professionals could be allowed to use their judgement, knowing the children and young people that they teach and take the time to be more flexible (and adaptive) in their approach to the curriculum, without being afraid of a backlash.

TTS has a wealth of resources to support children in all of these areas. Explore the full range here.

Additional support and references

- BDA – //www.bdadyslexia.org.uk/services/assessments/diagnostic-assessments/

- Dr Julia M. Carroll et al. ‘Towards a consensus on dyslexia: Findings from a Delphi study’ – //osf.io/preprints/osf/tb8mp_v1

- Nathan Hughes, University of Birmingham, UK; Murdoch Children’s Research Institute, Australia; University of Melbourne, Australia. The Howard League: ‘What is Justice?’ Working Papers 17/2015Howard League – //howardleague.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/04/HLWP_17_2015.pdf

- Neil MacKay – //www.actiondyslexia.co.uk/

- Jamie Oliver- Dyslexia Revolution – //www.channel4.com/programmes/jamies-dyslexia-revolution

- Dr Ailbhe O’Loughlin- //t2a.org.uk/2023/12/05/how-can-neurodiverse-children-and-young-people-be-prepared-for-the-transition-to-the-adult-estate/

- Penal System – www.theprisonreformtrust.org.uk

- Sir Jim Rose – //www.thedyslexia-spldtrust.org.uk/media/downloads/inline/the-rose-report.1294933674.pdf

With many thanks to Rachel Gelder and Pamela Hanigan from Lancashire Dyslexia, Information, Guidance and Support (LDIGS) for sharing this blog.

Rachel Gelder joined the NHS on leaving university, working in Oxford and London in a variety of management, project management and contract roles, eventually specialising in Mental Health, including time in Broadmoor Special Hospital. Whilst her two boys were young she decided a change of direction was needed. She moved north to live in Lancashire and into education. Rachel is a Specialist Dyslexia teacher and in 2014 formed Lancashire Dyslexia Information Guidance and Support (LDIGS) with Pamela Hanigan. This is balanced with her role as a SENCo in a mainstream primary school with high levels of special needs.

Pamela Hanigan began her teaching career in 1997, in Salford Education Authority. She has continued her passion for teaching and education throughout this time, teaching and tutoring children from nursery age to Year 11. Based for the past 17 years in Lancashire, her interest in supporting children with neurodiverse difficulties and particularly with the development of reading and phonics skills grew. Pamela is a Specialist Dyslexia teacher and assessor and in 2014 formed LDIGS (Lancashire Dyslexia, Information, Guidance and Support) with Rachel Gelder. The pair continue to balance their roles in their schools, together with assessing those with suspected dyslexia and supporting schools and other professionals, through training and consultancy work relating to dyslexia.