This month’s blog explores the principles for safe teaching and learning, and looks at some ways to deliver them.

Children should feel safe and secure and free of judgement in any lesson, but this is especially important for PSHE delivery. There may be sensitive content within topics (puberty and sex education probably come to mind immediately), but more generally the subject asks pupils to reflect on their own lives, behaviours, relationships and values, and consider personal feelings and emotions. It can therefore be at best ineffective and at worst harmful if pupils are not learning within a safe environment. A safe environment can also enable teachers to feel more relaxed and secure, and thus more confident, especially with those trickier topics.

What is a safe teaching and learning environment?

A safe environment sets expectations for behaviour so that all pupils can take part without feeling judged or shamed, and can consider issues, share opinions and ask questions with confidence – it is not about group counselling, or pupils having to share personal information. When these expectations are continually re-established and reinforced, pupils can progress in developing skills, attitudes and attributes that they can use beyond the classroom.

The following key principles, advocated by the PSHE Association, should be followed throughout all your primary PSHE teaching:

Set ground rules

Having ground rules means that pupils know the boundaries within which discussion and activity will take place. It’s important to agree these rules with pupils of all ages to enable a sense of investment in and ownership of them. You don’t even need to call them rules – you could just say ‘In this classroom we…’ or title them ‘What we do in PSHE’. The important thing is that pupils can understand and follow them, that they are reinforced in each lesson, and are revisited from time to time to keep them fresh and relevant. Having them on display can also be a useful reminder for pupils (and the teacher) to refer to when needed.

Some examples of ground rules in KS1:

- When someone is speaking we show we are listening to them.

- We can ask questions if we are not sure.

- We never say unkind things about other people or their families.

- You can tell someone if you feel worried or unhappy in a lesson.

Some examples in KS2:

- We listen to what others say.

- We speak to one another respectfully and kindly.

- No question is a bad question.

- You don’t have to share personal experiences.

- We don’t share other people’s experiences and information unless they say we can.

- You can speak to a teacher privately if you need to.

When teaching particular topics (e.g. within sex education), you may want to ask pupils if they think that there are any additional ground rules they would like, such as ‘use the correct name for parts of the body’ or ‘do not comment on the way someone looks or the choices they make’.

‘Distance’ Learning

Distancing learning enables pupils to consider a situation in a removed way. They may have had or be having a similar experience, but distancing means they can experience it objectively. This can help them tap in to the learning, implicitly or explicitly – for example, by considering how to help someone else in a particular situation they might then think of using those methods for themselves, or they may reframe a situation they are struggling with by thinking of it in objective terms (‘What would I tell someone if they were feeling like this?’ ‘What would I say if my friend asked me to help?’)

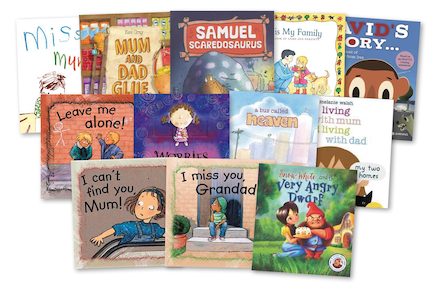

Picture books can be a very powerful way to distance learning for all ages, as they can present a situation and show someone’s journey through it. They can explore different characters’ challenges and behaviours and a whole spectrum of feelings and emotions, in an unthreatening way. They can introduce a topic or theme, be used to reinforce teaching points, or referenced as a reminder, even beyond the lesson (e.g. “Do you remember when Frog kept comparing himself to his friends? How did he find out what he was good at?” “When the girl was upset, what did her friend do to help her feel better?” “How had Dad changed by the end of the story?” You can also act out scenarios in picture books, predict, change or suggest different endings based on alternative behaviours, or, for older children, explore more in-depth issues such as diversity, values or confusing emotions.

Other good ways to distance learning with younger children include puppets and stuffed toys – e.g. Teddy has a problem and the pupils help her solve it. For older children you can use images, case study scenarios, ‘problem page’ emails, video clips, storyboards with thought bubbles, ‘hot-seating’ (with either pupils or teacher taking on a role and being questioned) or role play. With these last two, it is important that pupils ‘de-role’ afterwards, and that activity is carefully monitored so that they are not acting out stereotypical or aggressive behaviour.

Be sensitive and aware

You will know about vulnerable children in your class, and be aware of particular circumstances, but you cannot know what is going on in every child’s life. Being sensitive to vulnerabilities and lived experiences, even if they are unknown, is essential when exploring particular topics such as family relationships. Assume that at least one pupil will be affected by what you are teaching – this way you will be considering sensitivities in your planning. Certainly you should not ask pupils to share negative experiences, or single out individuals (e.g. “Put up your hand if you’ve been bullied”).

When choosing resources, consider the content and images they contain. You would avoid anything which might be upsetting, frightening or shocking, but steer clear of anything that uses shame as a method of changing behaviour (see ‘Further reading’ below), and resources that lack diversity or present groups in a stereotypical or negative way. Wherever possible, look for images that realistically reflect pupils’ lives. It is also essential to have a non-judgmental approach when teaching about unhealthy lifestyle habits and choices, as many children will not have influence or power over these.

Be open and responsive to questions

‘Tricky questions’ are what many people dread in PSHE lessons! However, this is precisely where such questions will arise – a safe environment means pupils will feel empowered to ask them. It is important to encourage and value questioning, and that you respond positively – being evasive or dismissive, or refusing to answer a question because it makes you feel uncomfortable might mean a child creates their own answer, or looks elsewhere, potentially from inappropriate sources. Others will also use your response to decide whether it is ok to ask their questions. Above all be honest, even if you don’t know the answer: you will gain more respect by saying “I don’t know the answer to that question, but I’ll find it out” than by not responding at all.

It can also help to have a way to allow pupils to ask questions anonymously, such as a question box or post-it wall. You can collect any questions through the week and respond to them all together in a lesson – this can also be a good way for you to prepare responses without being put on the spot.

Next month’s blog will explore ways to answer example tricky questions in more detail.

Provide support beyond the lesson

Make sure that pupils know how and where to get help, information or advice beyond a lesson, if they need it. This can be as simple as making yourself available, or identifying other members of staff, but it could also be directing them to appropriate external sources. Draw attention to any posters or support information around school, which should be displayed in an accessible way (e.g. on toilet doors, in a school library or at a child’s eye-level in communal areas), or, for older pupils, appropriate online sources (and share this information with parents and carers). Teach pupils how to ask for help – words and phrases they can use – in different situations, and to identify people they can trust.

Further reading:

- Why it is important to avoid inducing shock or fear during PSHE lessons (PSHE Association)

- Using relatable fiction in PSHE to help children understand themselves and literature (Teachwire)

- Booktrust themed booklists

Thank you very much to Lucy Marcovitch for sharing this third blog in the six part series for us.

Lucy is a writer and educator with over 25 years experience in education. She began her teaching career in Leeds primary schools, then moved into resource writing and development. She spent 10 years as the National Curriculum advisor for PSHE education, which included participating in two National curriculum reviews, and developing the first national guidance, training and assessment resources for the subject. Her consultancy work includes developing and writing classroom resources and guidance materials, and educator training and guidance for a variety of charities and commercial clients including the BBC, Teach First, Hopscotch Consulting and Discovery Education. She is a part-time lecturer on the Childhood, Youth and Education studies BA at Coventry University.