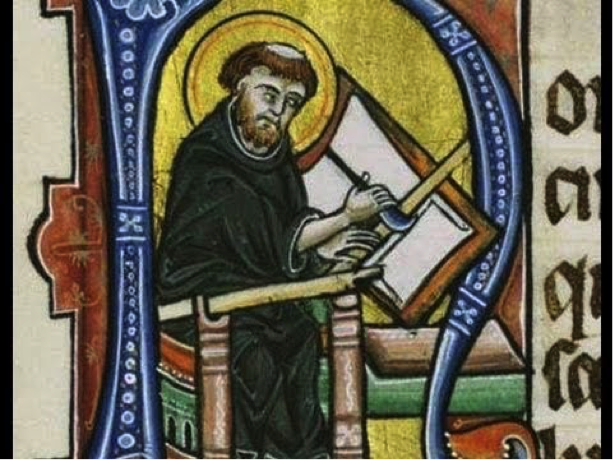

I was recently re-reading David Horspool’s biography of King Alfred the Great and I was struck by the different images of the King – ‘Great’ because he effectively resisted the Vikings, but also ‘Great’ because of his learning. It reminded me of the conflicting ways we usually teach the Anglo-Saxons – warriors and monks. I remembered a cold March day in Tallinn, Estonia, when I played truant from a conference session to visit a museum and came across this display of a monk copying out a book. What a tedious business, copying books by hand! As one monk wrote in the margin of a C9th Irish illuminated manuscript, ‘Thank God, it will soon be dark, writing is excessive drudgery. It crooks your back, it dims your sight, it twists your stomach and your sides.’ How many of our children would agree!

We usually imagine the Anglo-Saxons as invaders, from across the North Sea. But I wanted to explore the world of learning and ask a simple question – what can we learn about the Anglo-Saxons from ink? I know only a few people – mostly churchmen – were literate – but great store was placed on books. Where did the ink come from – after all you couldn’t just pop down the shops and buy a bottle of ink or a pen, could you?

I came across this medieval recipe for ink:

- Take a jar and fill it with eight pounds of rainwater.

- Add half a pound of small gallnuts and crush them.

- Put the jar on the fire and boil until the water with the gallnuts is reduced by half.

- Take three ounces of gum arabic and grind it.

- Add the gum to the mixture.

- Boil until reduced by half again and remove the jar from the fire.

- In a separate jar, take four ounces of vitriol and one pound of warm wine and mix them.

- Add the mixture little by little to the ink while stirring.

- Leave to rest for two days.

- After the two days, stir the ink everyday four times with a stick.

Of course, the monks wouldn’t make the ink; that’s what apprentices were for, but it still seems a very tedious business. The main ingredients are gallnuts; gum arabic; vitriol; wine and rainwater. Sometimes vinegar would replace the wine. But where do these ingredients come from?

Gallnuts come from the oak tree. Almost any oak tree may have gallnuts, depending on the season, but the finest were imported from around Aleppo, in Syria.

Gum Arabic is a gum from acacia trees. It either forms naturally, or is ‘tapped’ and collected like rubber. Once dried it can be ground down and used as a thickening agent in the ink, to make the writing more permanent. Gum Arabic comes either from Turkey or the Sahel region of Africa. If Gum Arabic was not available, fish glue or glair [made from whipped up egg whites, rather like meringue] could be used.

Vitriol is used to make the colour black. It is extracted from ferrous sulphate, and the best vitriol was imported from Spain.

Wine was imported from around the Mediterranean. So, just to make black ink you needed extensive trade links with Europe and Africa.

But what about coloured ink, used extensively in those beautiful illuminated manuscripts? How was that made, and where did the resources come from?

Just look at all the colours in this image of a monk copying a book.

Red ink was made from vermillion, which was mined in Spain, Egypt and the Balkans.

Blue ink was made from indigo from the woad plant, grown in any monastery garden, although the best ink was made from from Lapis Lazuli, mined only in Afghanistan.

Green ink used malachite, from the South of France, Israel, Central Africa, the Urals.

So next time you look at an Anglo-Saxon illuminated manuscript think not just about all the drudgery involved in copying it, but of the extensive trade networks needed to get the materials to the monastery where a very small boy would spend days mixing and pouring until the ink was ready to use!

With thanks to Alf Wilkinson for writing this blog post. Alf has taught History all his working life. Since 1999, Alf has been involved in CPD, both primary and secondary, having played a prominent role in the Historical Association’s response to each of the last two History national curricula. Over the last 2 years he has written schemes of work and been involved in the relaunch of the HA’s Journal, Primary History, as well as developing lots of innovative products with TTS to support teachers and spent lots of time with primary teachers exploring the implications of the new History curriculum.