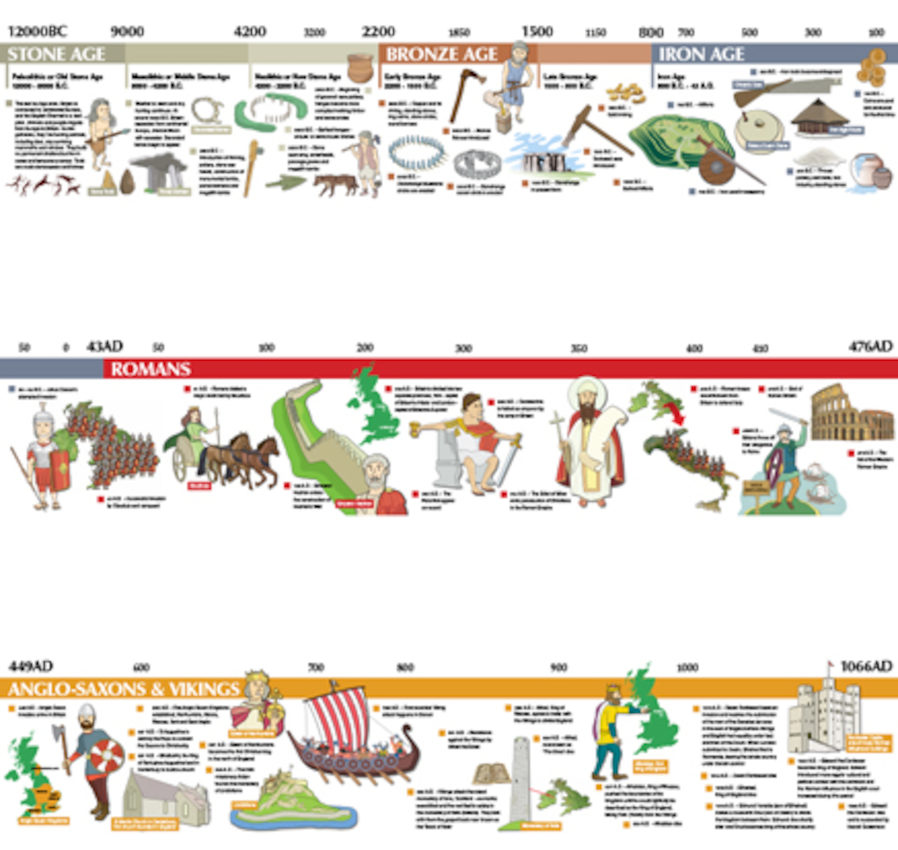

One of the real problems in history is trying to help children see the ‘bigger picture’ rather than just the topic they are studying. How does one topic – say the Anglo-Saxons – relate to another – say the Vikings? How do we portray the fact that although the Anglo-Saxons came to Britain first, there was still a strong vibrant Anglo-Saxon culture that carried on – often in conflict with the Vikings but sometimes side by side – right through until 1066 and the arrival of the Normans?

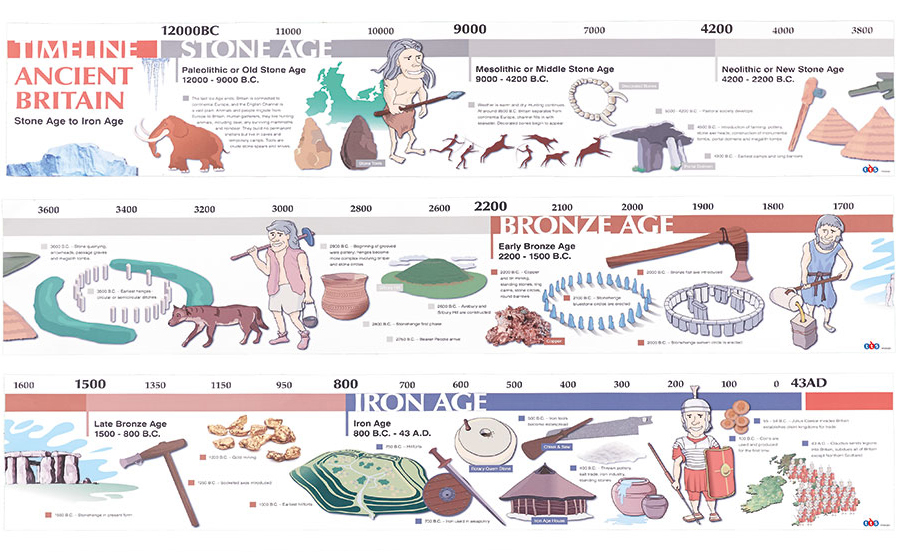

This of course is where timelines come in. They can show the sequence of events and how they relate to each other really well. With carefully chosen images they can show the continuities as well as the changes. After all for most people, for most of the time, the main preoccupations were having enough to eat, shelter, work and safety. In other words, survival! TTS has a wide range of timelines you can buy for use, either in children’s books, on the desk or on the wall of your classroom, indeed around the school hall. You could even paint one on your playground! We ought to use them much more than we do. They can also be used cumulatively, adding events from each topic as you study it, thus helping children to see how the Maya, for example, relate to the Anglo-Saxons and Vikings.

One of the issues I have with some timelines is that they compress time, rather than show it relationally. Sometimes a timeline will use exactly the same amount of space for the Stone Age to Iron Age [10,000 years] as it uses for the Anglo-Saxons [600 years.] Not only does this distort history, it also makes it very difficult for children to understand the passing of time, and how the events of one history period relate to another. Timelines, to be effective, really need to be to scale.

But chronological understanding is not just about sequence. It is also about a ‘feel’ for the period. What was it really like being a Roman soldier guarding the edge of Empire on Hadrian’s Wall in 150AD? What did they eat? What did they write home? What did they do when they were not being a soldier? In other words, how did they spend their time when they were being ordinary human beings rather than Roman soldiers? What does a Roman oil lamp, for example, look like? How does it work? How much light does it give out? Does it smell? Would that mean people went to bed when it got dark? That’s what I mean by a ‘sense of period.’

This is also where visits and living history come in to the picture. I always remember bumping into one of my ex-students, about 15 years after he had left school, and his first comment to me was “Do you still have that Roman soldier come into school and showing off his armour?” He had developed a life-long passion for history from one day with a Roman re-enactor. You can’t measure that with SATS!

With thanks to Alf Wilkinson for writing this blog post. Alf has taught History all his working life. Since 1999, Alf has been involved in CPD, both primary and secondary, having played a prominent role in the Historical Association’s response to each of the last two History national curricula. Over the last 2 years he has written schemes of work and been involved in the relaunch of the HA’s Journal, Primary History, as well as developing lots of innovative products with TTS to support teachers and spent lots of time with primary teachers exploring the implications of the new History curriculum.